Chinese scientists have devised an organic so-called molecular hard drive for archiving with multi-bit encrypted storage molecules written and read using an atomic force microscope.

The notion is presented in a Nature paper, Molecular HDD logic for encrypted massive data storage, published in February, and says “molecular electronics distinguish themselves with extreme potential for ultrahigh density information storage and logic applications.”

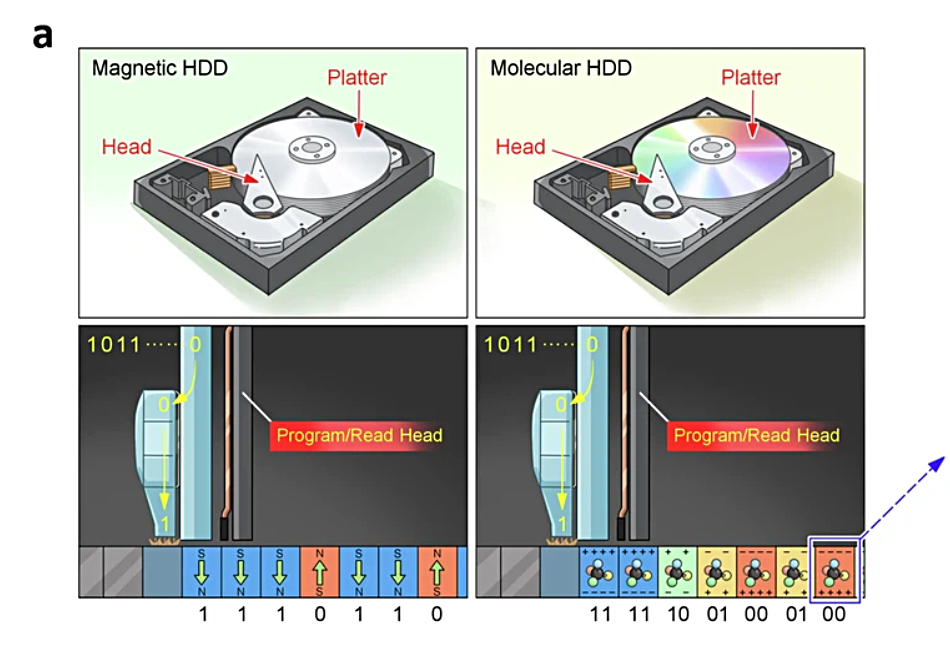

The basic HDD unit consists of ~200 organometallic complex molecules (OCM) deployed in a self-assembly monolayer (SAM) configuration. They are read and written with a conductive atomic force microscope (C-AFM) tip, which has a front-end radius of 25 nm. Digital information is written by altering the physiochemical states of the molecules, stored as the molecules’ redox (reduction-oxidation) and ion accumulation state, and read by sensing tiny bit currents in the material.

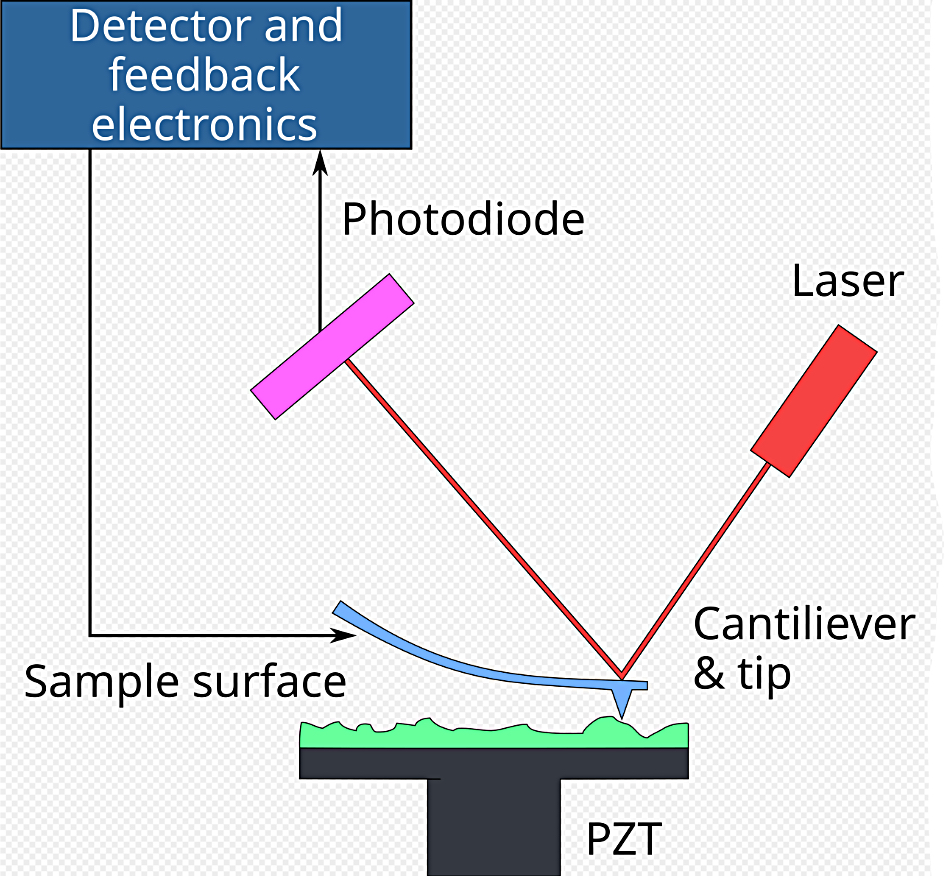

A C-AFM tip is used in high-resolution scanning to touch and measure the surface height of material at the nanoscale and also its electrical conductance. The tip is on the end of a cantilever and moves up and down as the surface is passed below it. A mirror on top of the cantilever moves, altering the reflected position of a laser beam directed at it, indicating the tip’s deflections. The reflected laser light is measured by a photodiode.

A voltage is applied between the tip and the sampled material, and local picoampere-to microampere scale electrical currents are measured.

The data-carrying molecules are made from “redox-active transitional metal cation (Rux+), organic ligands of carbazolyl terpyridine (CTP) and terpyridyl phosphonate (TPP), as well as driftable halogen anions (Cl−),” referred to as RuXLPH.

Ligands are ions or neutral molecules that bond to a central metal atom or ion. An ion is an atom or molecule that has lost or gained one or more electrons and so has a net electric charge. A cation is a positively charged ion and an anion is a negatively charged one. This means that a redox-active transition metal cation is a positively charged ion of a transition metal, ruthenium (RU) in this case, that can gain or lose electrons in a redox reaction. The “Rux+“ expression denotes a positive charge (+) with the X indicating the +2 to +8 oxidation state.

This molecule can have up to 96 conductance states, roughly equivalent to the voltage states in multi-level cell NAND. Hexa-level cell NAND has 6 bits and 64 states, and hepta-level cell flash has 7 bits and 128 states. The 96 conductance states “enables at least 6-bit storage for high-density data archiving applications.” This means, the researchers say, “the disk volume required to store the same amount of information with the RuXLPH monolayer based molecular HDD can be effectively reduced to 16.7 percent (1/6), in comparison to that of the traditional binary magnetic hard disks.” This is on a per-platter basis.

Even more conductance states could be achieved, increasing the bit level further. The device the researchers envisage has “ultralow power consumption of pW/bit range.”

Diagrams in the paper illustrate the researchers’ concept:

The paper discusses applying encryption to the stored data for enhanced security. They also envisage a reinvented floppy disk. “In the future, combining the deliberate molecular design cum synthesis strategy, partitioned assembling of customized molecules, and use of flexible substrates, the molecular HDD may even evolve into floppy disks for high-density, high-security portable digital gadgets.”

Comment

The researchers hold out the prospect of a disk-based storage system matching or exceeding tape archive density. However, the working life of an atomic force microscope tip is currently measured at 50-200 hours in intermittent touch (tapping) mode versus 5-50 hours in continuous touch mode.

Unless and until a long-lasting C-AFM tip can be created, this would seem to be a fatal flaw in their molecular hard drive concept.

A second point is that the device has “ultralow power consumption of pW/bit range,” but this is for reading and writing, not spinning the disk, which would take more power.